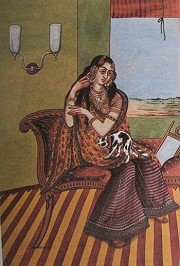

This story originally appeared in CATFANTASTIC 5. The inspiration for this was an Indian miniature painting from around 1800 called "The Courtesan Who Loved Cats", which showed an ornately dressed woman with a small black and white cat in her lap.

This story originally appeared in CATFANTASTIC 5. The inspiration for this was an Indian miniature painting from around 1800 called "The Courtesan Who Loved Cats", which showed an ornately dressed woman with a small black and white cat in her lap.Although late, the monsoon had come at last to break summer's fearful heat. Marjari stood beside the peacock window in her room in the House of Nine Jewels, staring out at the steady rain and idly stroking her favorite pet. The black-and-white cat pressed against Marjari's body, a warmly vibrating bundle of soft fur and hard muscle. The cat's purr created a gentle counterpoint to the harsh music of the silver rain.

Harsh music indeed. But I should savor its sound; when it ceases, he will come and I must smile, and persuade him to be generous...and he is not a generous man.

Sighing, Marjari set the little cat upon the window ledge and leaned out into the heavy monsoon rain. Water poured warm over her face, streaking the kohl outlining her dark eyes and blurring the view of the city beyond as if she stared through tears.

He knows about the child; he knows, and yet says nothing. It is his, he must acknowledge that, and give me money, for if he does not -- If her patron did not support the child, Ugrata-Ma, owner of the House of Nine Jewels, would have the infant poisoned with opium or flung into the street for the pi-dogs to devour. Only the hope of favors from the foreigner had kept Ugrata-Ma from taking swift action to prevent the child's birth.

But it was becoming obvious to the ruler of the House of Nine Jewels that Marjari's patron would not pay more to ensure life for the child he had fathered. And now it was far too late for any jadu's potions to ease Marjari of her burden of new life. The child would be born soon, and then it would die; there was no place for useless infants in the House of Nine Jewels....

And I cannot bear to give birth to a child only to see it die. Tears mingled with rain upon Marjari's cheeks; beside her, the black-and-white cat leaned against Marjari's arm, patted her wet face with a silk-soft paw.

Half-smiling, Marjari caught the worried cat up in her arms. "You try to comfort me, like the true friend you are." Of all the many cats Marjari fed, this little one was her darling; her companion during forlorn days and cruel nights. Marjari kissed the top of the cat's silk-furred head and scratched its delicate jaw. The cat purred, whiskers bristling like slender sword-blades.

"Perhaps you are right," Marjari told the cat, "perhaps he will be kind. Perhaps--"

"Perhaps what, my pet?" As usual, her foreign patron had entered unannounced, striding in without permitting Marjari even a moment to prepare herself. Smiling with professional ease, Marjari allowed the cat to flow out of her arms to the floor.

"I am pleased that you have come at last, my lord. That is all." Marjari moved forward to take his hat, and his coat; long practice enabled her to ignore the harsh scent of the meat-eater emanating from his skin.

"Missed me, I see." His voice was as harsh as his scent, his words clipped and discordant. He handed Marjari his oddly-shaped hat, but then shrugged her away, refusing to permit her to remove his coat.

"Of course, my lord." Marjari laid his hat upon a painted chest, then faced him, studying his strange pink-tinged skin and pale opaque eyes, hoping to find some kindness lurking there. But his alien face told her nothing.

Summoning all her courage, Marjari smiled and laid her hand upon his arm. "How could I not miss the father of my child?" she asked.

He frowned and shook off her soft hand. "Not that again! Now see here, girl -- I've told you before this brat's none of my concern. If it's mine at all! You're a common whore; how do I know how many other men you've had to your bed?"

Gasping at the insult, Marjari drew herself up and met his hostile eyes bravely. "I am not a whore, my lord -- what you have paid for has been yours alone."

"So you say." He scowled, and kicked absently at the edge of the small Turkish carpet beside her bed. "I say you're a lying whore."

Marjari gasped again, and beside her the black-and-white cat growled low in its throat. The cat did not like the foreign man who came so frequently and pawed the cat's mistress; he smelled vile and sounded rabid. And he made the cat's mistress weep, and the cat did not like that either.

"Damn it, girl, stop wailing at me like -- like a damn alley cat. You can send me a note after the brat's born, and I'll come see you and bring you a present -- when you've got your looks back, that is."

Grabbing up his hat from the painted chest, the man turned away, and Marjari realized he was leaving their child to whatever fate Ugrata-Ma decreed for it. "No!" she cried, and ran to clutch at his arm. "No, you must -- "

The foreign man rounded on her, growling like a mad dog. "Damn you, stop pawing me!" He shoved Marjari away; awkward with the burden of her unborn child, she stumbled backwards, nearly treading upon the black-and-white cat's tail.

The man followed, and loomed over her. "Now listen to me, girl -- you've had your fun and your money, now leave me alone." To emphasize this command, he grabbed Marjari's arm and shook her.

It was too much. Angered, the black-and-white cat slashed at his ankles. Claws like tiny scimitars ripped through the man's trousers and into pallid flesh. But the cat's claws, fully extended, caught upon cloth, and it could not pull its paw free--

Releasing Marjari's arm, the foreign man swore, his words a loud snapping like the barks of pi-dogs. "Damned cat -- nasty sly beast -- just like a woman -- " As he snarled and swore, he bent, reaching for the trapped cat. "I'll take care of you, you bloody cat -- "

Crying out, Marjari rushed forward. But she was too late; the man grabbed the little black-and-white cat by the scruff of its neck and hurled it from him. There was a small harsh thud as the cat's body hit the wall beside the aloe-wood almirah.

Marjari stooped beside the limp body and stroked the cat's soft fur. There was no response, and Marjari glared up at the man as tears streaked black kohl down over her flushed cheeks.

"You have killed it," she accused.

"Oh, stop sniveling, woman -- it was a damned nasty, sneaking beast that wouldn't waste an eye-blink over you. Not like a dog. Now a dog knows how to be loyal. Faithful. Not like a cat -- or a woman," he added, strolling over to gaze down at Marjari as she crouched beside the body of the little cat.

"Besides, the alleyway's full of the damned animals. Now leave it lie, and come show me how well you can please me, and maybe I'll let you have another. I don't mind a kitten," he added magnanimously. "A kitten's a suitable pet for a woman, if it's a pretty one. But no more damn cats, do you understand me?"

Marjari understood. She understood that to the man, she herself was of no more importance than the little cat he'd slain, and the child they had created together would be of less importance to him than a pretty kitten.... Marjari let her hand rest for a moment upon the cooling body of the cat, and then rose to her feet and stared at him.

"You are an evil man," Marjari told him in a cool, clear voice, "and you will be punished for what you have done today. Now leave me, for I am done with you."

"But I'm not done with you," the man said, and grabbed Marjari by her braided and jeweled hair. She fought him, using her gilded nails to rip his cheeks and her sharp teeth to bite his grasping hands.

"Damned bitch!" he barked, and slammed his fist into Marjari's temple, sending her staggering back. His second blow beat her to her knees, and his third to the floor to lie beside the body of the black-and-white cat. The man stood silent for a moment, breathing heavily and glaring at the fallen creatures. Then he stalked over, stiff-legged with fury, and kicked Marjari's rounded belly.

"Damned bitch," he repeated, and then kicked the cat's body for good measure.

The cat knew that she was dead; she hovered beside Marjari, waiting for the courtesan's ghost to rise and accompany her. But the courtesan was not yet dead, and the cat was alone, a ghost watching a woman die.

She will die, as I have done, and that man walks free -- no! With all the strength of her heart, the cat called upon the Lady of Cats, a demanding, desperate prayer whose wail caught the Lady's attention even through the prayers of women in childbed and mothers in sickrooms.

Help me, the cat cried. Hear me, help me, help my mistress who dies, and her unborn child with her!

"I hear you," a voice answered, and Shasti, goddess of childbirth, and children, and not least, of cats, stooped to stroke the cat-ghost's back. "How may I help you, my kitten?"

"My mistress dies, slain as I am by the man who used her body and fathered her child and cast her into shadows."

"Yes," said the goddess, "I know. But I cannot undo what has been done. Perhaps I can save the child, if any think to call upon me as it is born."

"They will not, for they care nothing for my mistress, and will care less for her child, who will be worth nothing to them." The cat trembled under the goddess's caressing hand. "Help me, Lady, and I will be always grateful."

The cat stropped nervously against the goddess's ankles, and Shasti smiled. "You have called upon me, my kitten; of course I will aid you. But it will take greater powers than mine to unknot this snarl." The goddess reached out and lifted the little cat into her arms. "Come then, my kitten, and we will ask your boon of the Lord of Death."

Carrying the black-and-white cat in her arms, the goddess walked south, along the road to the Land of the Dead. The goddess walked steadily, pausing for nothing. Even when they passed the Lord of Death's two guardians, and the four-eyed dogs glared and growled low in their throats, Shasti did not falter. And when the cat hissed and bristled at the dogs, the goddess bade the cat be silent, and was obeyed.

At last the goddess Shasti came to the end of the road south. A bronze palace rose up before them, and the goddess walked calmly through its brazen gates and through its iron halls until she stood before the throne of judgment where Lord Death sat in his blood-red robes. There Shasti stopped, and set the cat down beside her feet, and bowed.

"Greetings, Lord Yama," the goddess Shasti said. "I bring a soul who would ask a boon of you."

"What boon?" the Lord of Death demanded in a voice that boomed like a brass gong. "I judge fairly, and grant no favors."

Shasti nudged the little cat with her foot, and the cat stepped forward, her paws moving daintily over the iron floor. The cat looked up into Lord Yama's green-skinned face and met his copper eyes boldly.

"Listen, then, Lord Yama," the cat said, "and judge fairly." And then the black-and-white cat told Lord Death the tale of her sweet mistress, the Courtesan Who Loved Cats, and what the foreign devil had done to her.

"A sad tale," Yama agreed, "but I hear many sad tales from those who pass before me. I will not alter what has been done. You are dead, cat, and your mistress dying; she too will soon stand before me and hear her deeds read out and judged."

"I know I am dead," said the cat, flexing her claws. "I do not ask you to change what has been."

"What do you ask then, cat?"

"Justice," the little cat said. "Give me a life in which I may avenge two murders, and send the murderer to judgment."

Lord Yama thought for a moment, and then turned to his Recorder of the Deeds of the Living. "Chitragupta, read out to me the list of this cat's virtues and sins."

Chitragupta opened a great book and peered along its endless pages. "It is but a short list, Lord Yama. It says only that she possesses all a cat's sins -- and all of a cat's virtues."

"And a cat's virtues are well-known," the goddess Shasti added softly. "So judge fairly, Lord Yama; three souls rest in your hand."

At last Lord Yama nodded his terrible head. "Your request is fair, cat. I will grant what you ask. The Lady Shasti will take you back to the middle world so you do not lose your way upon the journey. Now go," the Lord of Death instructed, "and return swiftly, or you will not reach the living world in time to claim your new life."

Marjari's daughter slipped into life just as Marjari herself slipped out of it. Ignoring the dead woman, the old midwife who had been hastily summoned by Ugrata-Ma concentrated her efforts upon preserving the newborn girl. After all the years and all the children she had brought into the uncaring world, the midwife possessed certain gifts of prophecy.

"She will be special, this one," the midwife said, wiping the silent infant clean with Marjari's second-best veil. "She will be a beauty."

And, trusting the old midwife's judgment, Ugrata-Ma decided to let Marjari's daughter live, and set the opium bottle back in her sandalwood chest. The poison would keep for use on another occasion.

When first she opened her human eyes, they glowed soft milky blue, like those of a week-old kitten. As she grew, the blue deepened and hardened until her eyes shone a clear true green, like the eyes of a cat. Those green eyes named her, when she grew too old to be simply called 'Lali' -- 'little jewel' -- like all the other little girls dwelling in the House of Nine Jewels.

Cat-eyes.

Cat-eyes grew swiftly towards womanhood, as if some inner goad urged her to maturity. Although cool and aloof, and far too fond of her own way for Ugrata-Ma's liking, the girl lapped up knowledge as if it alone would make her fortune. By the time she was twelve, Cat-eyes possessed all the skills she required, and more besides.

She knew how to paint her face to skillfully enhance her slanting eyes and her small prim mouth. She knew how to select veils to set off the whiteness of her skin and bright jewels to highlight the blackness of her hair. She could recite amorous love lyrics, epic poems, and riddles. She could tell fortunes, and play chess.

She could sing in a pure clear voice, and she knew all the appropriate ragas and ghazals, and when each should be sung, and how, and why.

And she could dance -- and when Cat-eyes danced, even the most arrogant of the House's bartered Jewels stopped to stare, entranced, as Cat-eyes arched and swayed across silken carpets, her garments flowing about her like wayward leaves.

She had learned cruel skills, too; the crafts of perfumes and poisons. But these dark talents were hers alone. Ugrata-Ma did not know all that Cat-eyes knew.

And one day, Ugrata pronounced Cat-eyes ready, and Cat-eyes smiled.

Cat-eyes had been ready for a long time.

As with so many who dwelt in the half-world between destitution and respectability, Ugrata-Ma was a great believer in tradition. Tradition decreed that a newly-unveiled jewel sing and dance before those who would then bargain for her charms. For Cat-eyes's first night before men, Ugrata-Ma outdid herself: the inner courtyard of the House of Nine Jewels became a dream of desire, a false garden perfumed by jasmine garlands coiled about the chunam pillars and China roses in silver bowls. For once, lavish expenditure did not trouble Ugrata; the courtesan Cat-eyes would lavishly repay the generosity shown by the House of Nine Jewels.

Ugrata-Ma had selected those who were to attend the evening's entertainment with the utmost care, restricting the guests to the city's most affluent and influential men. She was surprised when the foreigner arrived, for she had not invited him -- not this time. But he came riding up alone to the door of the House of Nine Jewels, dismounted, and casually tossed his horse's reins towards Ugrata-Ma's doorkeeper, a pious man who hastily summoned a waiting urchin to hold the leather strips.

"I hear you've something new to show," the foreign man said, and Ugrata-Ma bowed, hastily recalculating. Foreign men were difficult at times, but this one was rich -- rich enough to buy blind eyes and new playthings after his coarse hands had killed the Courtesan Who Loved Cats. But her death had been a long-ago accident, and Ugrata-Ma cultivated forgetfulness like a rare flower.

Now she smiled and invited the foreigner across the threshold into the inner courtyard -- and forgot to wonder who had invited him to attend this special night at the House of Nine Jewels.

Behind a pierced and gilded ebony screen, Cat-eyes stood watching as Ugrata-Ma escorted the foreign man to the best seat in the courtyard. "A chair," Ugrata-Ma ordered as the foreigner stared disdainfully at the cushions elegantly-arranged by the servants for a man's comfort. A chair -- a foolish, uncomfortable seat, suitable only for a barbarian -- was brought, and the foreign man sat, folding himself upon the chair in a series of awkward lurches.

The man who once had killed a courtesan and her little cat had come at last.

As Cat-eyes had known he would come when she carefully inscribed the letter that had invited him here tonight.

He was neither so young nor so handsome as he had been fourteen years before. Sun had burned him red as Lord Yama's robes; wine had coarsened and blurred the lines of his face; time had faded his once-bright hair.

But nothing could alter his stone-pale eyes. Unseen, Cat-eyes stared at those foreign eyes; her veil twitched as her henna-painted fingers toyed with the glittering fabric, and her neat pink tongue licked her reddened lips.

"Do not be nervous, child." Fussy as an old hen, Ugrata-Ma adjusted a strand of pearls lying across Cat-eyes's breast. Ugrata-Ma's fingers trembled, and the pearls rattled softly, a sound like raindrops upon leaves.

"I am not nervous," Cat-eyes said, ignoring her mentor's fretting.

"You are the most precious of my jewels -- you are perfection itself."

"Yes," said Cat-eyes, "I know." And then she waited until Ugrata-Ma bustled off to sit beside her most important guests; waited, still as stone, until it was time to walk out from behind the ebony screen into the flower-decked courtyard.

To walk out before the waiting men, and dance.

Within the courtyard the air was hot and still, the scent of roses and jasmine heavy as smoke. Cat-eyes walked across a carpet of velvet soft as spring grass beneath her henna-painted feet. At the center of the court, she paused, her eyes cast modestly down, waiting still and poised as a goddess...and a heartbeat before the music began, Cat-eyes looked up, and stared into the foreign man's cruel eyes.

And then the music began to swirl through the heated air, and slowly, sensuously, Cat-eyes began to dance.

At first her masculine audience murmured with delight as they watched. But gradually, almost imperceptibly, the sounds of approbation ceased, dying away until the only sound within the courtyard was the languid swirl of music and the chime of gold against gem as Cat-eyes danced.

Fluid as sunlight, she wove across the Persian carpet, light and joyous as a cat dancing after a butterfly in a harem garden.

Graceful as moonlight, she drifted like incense and passion's sighs through the perfumed air.

Supple as midnight, she flowed within the music, a carnal shadow to the love-song's pure ardent cries.

And as she danced, Cat-eyes never lifted her intent hunting gaze from the foreign man's avid, greedy face.

The foreign man wanted her; that outcome had been ordained long before Cat-eyes set her pretty foot upon the velvet garden spread before him. The only question was that of price -- and whatever Ugrata-Ma asked, Cat-eyes knew the foreigner would pay.

Cat-eyes remained seated in the final pose of the lovers' dance, motionless as a waiting cat, as Ugrata-Ma feigned doubt and misgivings, and the man responded in harsh, urgent tones.

At last Ugrata-Ma yielded to his persuasions, and beckoned. At the signal, Cat-eyes rose and padded over to the dais, setting each foot so gently upon the Persian carpet that the silver bangles about her ankles made no sound. Cat-eyes bowed before the man who wished to become her master and touched her smooth forehead to his leather-shot foot.

"Pretty little thing," the foreign man said, lifting Cat-eyes' pointed chin with his toe so he could look into her skillfully-painted face. "Well-trained, too," he added approvingly, and bent forward to pat Cat-eyes upon her cool cheek. "Had a dog like that once."

Ugrata-Ma smiled politely, and -- most discreetly -- opened negotiations for this most glittering prize of all her costly Jewels.

And so the arrangement was made. Cat-eyes herself took no part in the bargaining that followed; she knew the outcome, for she knew that until the foreign man possessed her, his desire for that possession would overrule other lusts. She need not fear that he would refuse to pay what Ugrata-Ma asked. And Cat-eyes had her own preparations to make before the night their passions would be consummated.

Cat-eyes studied her long, elegantly-filed nails, and smiled like a cat in sunlight.

Tonight he would come, and she would be ready for him.

She had dressed for the great occasion with exquisite care, each choice, each selection, flawless and deliberate. Now she shimmered in silks of midnight and moonglow, a phantom in ebony and ivory. Black and white; a strange choice for a courtesan's first night. But Cat-eyes had insisted, and Cat-eyes had a knack for getting her own way.

Black and white, for memory. And now red, for luck....

Cat-eyes touched her forefinger to the sindur powder in its alabaster jar and then pressed the reddened fingertip to the smooth skin of her forehead. Tilting her head, Cat-eyes inspected her face in the ivory-backed mirror. The luck-spot gleamed between the black crescent moons of her brows like fresh blood.

Perfect. I am perfect. Smiling a cat's small smile, Cat-eyes laid the mirror down again upon the sandalwood table. She was perfect, and perfectly ready for tonight's events.

It has been fourteen years since you slew the Courtesan who Loved Cats, foreign lord. Fourteen years you have gone unpunished for your sins. Cat-eyes smiled again, and her teeth shone ivory-keen against the crimson of her painted lips. Now, dog, you will learn the faithfulness of cats.

Beyond the sandalwood door, she heard heavy footfalls and heavier breathing; the mingled smells of whiskey and carnivore's rank sweat seeped through the lattice. Cat-eyes wrinkled her nose in distaste, then schooled her expression to one of modest welcome. It was a simple matter, for the ruse need only fool a man.

Eyes cast meekly down, lashes masking cunning green eyes. Mouth curved in a goddess's serene smile. Hands folded placidly in her lap, half-hidden by the misty folds of her veil. As the door slowly opened, Cat-eyes permitted her henna-rose fingers to stretch and curve, as a hunting cat might flex its velvet-sheathed paws.

In the soft breath of wind from the opening door, lamplight danced and shadows flickered. The little flames within the pierced lovers' lamps scattered about the room flared tiger-bright.

And in the light of those shadowed flames, Cat-eyes' freshly gilded and poisoned nails flashed long and sharp as claws.